The Great Squirrel Stampede

The Great Squirrel Stampede

By: David Heighway, Hamilton County Historian

For being such a small and innocuous animal, the common squirrel has aroused a great deal of animosity through the years. Its cleverness and persistence in getting food has naturally antagonized anyone who might want to keep some food for their own use. Any person that has ever owned a birdfeeder would understand the pioneers’ frustration at being unable to keep squirrels out of their gardens and cornfields. However, in the early part of the 19th century, it was not feeder acrobatics that threatened the humans’ food stores. It was sheer numbers of animals. While almost forgotten now, the enormous waves of squirrels that swept across the United States in the 1800’s were as much concern at that time as locust or disease.

In 1901, Noblesville lawyer Augustus F. Shirts (1824-1905) wrote a book called A History of the Formation, Settlement, and Development of Hamilton County, Indiana, From the Year 1818 to the Close of the Civil War. It was devoted largely to stories about pioneer life in this county. One story went as follows:

[blockquote text=’“In the year of 1826 the great emigration of squirrels occurred. The squirrels passed through this county from west to east. The number could not be estimated. The time occupied in passing was about two weeks. They destroyed all the corn in the fields they passed over. They could not be turned in their course, but went straight on in the route taken. When they came to White River they entered the water at once and swam across. Hundreds of them were shot. Others were killed with clubs and stones. It was never known from whence they came or where they went.”’ text_color=’#8dc63f’ width=” line_height=’undefined’ background_color=” border_color=” show_quote_icon=’no’ quote_icon_color=”]

At one time this was dismissed as folklore, but since Mr. Shirts’ parents were among the first settlers of Hamilton County, he probably heard it first-hand. Allowing for some discrepancy in dates, there are plenty of eyewitnesses to this flood of rodents, as well as modern scientific justification.

One eyewitness was Calvin Fletcher (1798-1866), an Indianapolis lawyer, banker, and civic leader who kept a diary throughout most of his adult life.[i] Combined with his letters, this is an excellent resource for early central Indiana history. In a letter to his brother dated February 23, 1823, he states:

[blockquote text=’“The corn this year was literally destroyed, unless in the prairies, by grey and black squirrel. Sir, there was by one man killed round one cornfield 248 in 3 days about 4 miles of this place. Many people lost whole cornfields – 12 squirrels were supposed to destroy as much corn as one hog. They eat only the heart or pit of the kernel. The squirrel appeared to be emigrating towards the S.W. instead of the E. as he has always done heretofore. The reason for his emigration this year was this – our woods or wilderness, it scarcely ever fails to produce a sufficient quantity of mast to support such vermin but this year they entirely fail’d – the word mast is used by the people here for the fruit and nuts that grow on forest trees.”’ text_color=’#8dc63f’ width=” line_height=’undefined’ background_color=” border_color=” show_quote_icon=’no’ quote_icon_color=”]

Another first-hand observer was Oliver Johnson (1821-1907). He lived in a cabin that his parents built in 1822 at what is now 38th Street and Fall Creek Boulevard in Indianapolis. In his later years, he reminisced about his early life to his grandson, Howard, who wrote down his tales under the title A Home in the Woods.[ii] He told many stories about hunting, including the following:

[blockquote text=’ “Squirrels were always so plentiful that we saved only the choice parts: the hams and the back. We always shot a squirrel in the head so that the bullet wouldn’t spoil those parts. In the fall we nearly always had a spell of travelin’ squirrels. We supposed that the mast and nuts that they fed on was scarce in some sections and caused them to move on to other places where they could find something to eat. One fall there was so many passin’ through they became a pest, makin’ raids on the corn fields. They come by the thousands for several days. They was so starved and footsore from travelin’ that they wasn’t fit to eat. Pap said something had to be done, so he put Uncle Milt and me to patrollin’ the corn field with our rifles. At night we would mould enough bullets to keep us shootin’ all the next day. The squirrels was so hungry they didn’t scare very much, but the crack of the rifles helped to keep them up in the trees. One day I counted eighteen dead squirrels I shot from a tree without changin’ position or missin’ a shot. We left so many dead ones on the ground that they actually attracted the buzzards. We saved most of our corn that fall, but some neighbors who didn’t patrol their fields had their corn eat up so bad it didn’t pay to gather it.”’ text_color=’#8dc63f’ width=” line_height=’undefined’ background_color=” border_color=” show_quote_icon=’no’ quote_icon_color=”]

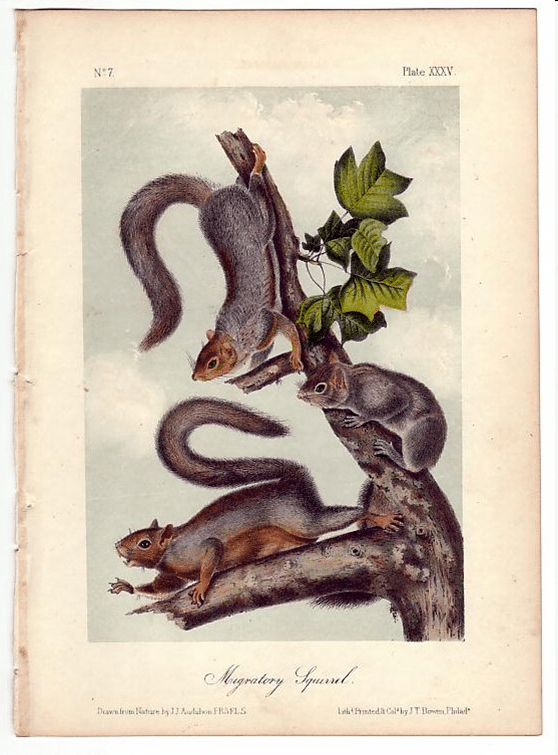

John James Audubon (1785-1851) is considered one of the greatest naturalists America ever produced. He witnessed several great squirrel emigrations, including ones that crossed the Ohio and Hudson rivers. He was impressed with their ability to swim or to grab floating objects in their effort to reach the other shore, even though many drowned. In his 1846 book, Viviparous Quadrupeds of North America, he said “The farmers in the Western wilds regard them with sensations which may be compared to the anxious apprehensions of the Eastern nations at the sight of the devouring locust.” However, he made an error about the squirrels when he declared the Migratory Squirrel to be a separate species. It was actually the common Gray Squirrel (Sciurus carolinensis) that Audubon saw swimming the rivers.

According to some early Indiana histories, there were two great squirrel emigrations in central Indiana, 1822 and 1845. There were other smaller movements in various parts of the state in the early 19th century.[iii] Nationally, there were several multi-state emigrations, including an enormous one in 1842 that that swept from Iowa to Wisconsin. Rough descriptions suggest it was 130 miles wide by 150 miles long. One person viewing an area of road only a few yards wide guessed he could see 1400 animals. A modern scientist estimated that the emigration contained half a billion squirrels.[iv]

Naturalists contend that the regular emigration of small groups of squirrels is a form of population dispersal. The movements are referred to as “emigrations” because, unlike a migration, the animals do not return to the home country. Experts call the annual autumn emigration the “fall shuffle”. They are not certain what would cause the larger movements, although one scientist suggested flea infestations! Most naturalists think environmental pressure seems to be an obvious answer. The large emigrations usually occurred when a time of plentiful food was followed by a time of scarce food.[v]

Presumably, these emigrations had gone on for centuries. Prior to settlement by Europeans, the area east of the Mississippi River was covered in an almost continuous forest. Squirrels could swarm from the Atlantic coast to the Mississippi and never have to touch the ground. Although the Native Americans were probably aware of these movements, (which would have been very useful for hunting), their reaction was not recorded. The emigrations first began to be noticed when the settlers moved in and began clearing the forest. A mob of starving squirrels that suddenly came upon a cornfield would have a very obvious reaction. However, as more forests disappeared, the squirrels’ habitats and mobility were greatly altered.

Reports of large emigrations have become almost non-existent in the United States today. One was reported in the eastern U.S. in 1968 and another occurred near Lake Michigan in 1985. Estimates of numbers of animals are based on the amount of road kill left behind. The feeling among scientists is that the environment has been changed so profoundly that the squirrels’ behavior has changed in response. And while is it unlikely that they will ever be put on the endangered species list, the population of squirrels today is smaller than in the 1800’s. With less pressure on the food supply, they have become more sedentary.[vi] In all probability, the sight of great herds of squirrels swarming through the trees and cornfields is now a thing of the past. So the next time you throw a few curses at the furry-tailed thief in your birdfeeder, be grateful for the fact that he hasn’t brought several thousand of his friends with him.

[i] Calvin Fletcher, The Diary of Calvin Fletcher: Vol. I, 1817-1838 (Indianapolis, Ind., Indiana Historical Society, 1972), p. 88.

[ii] Howard Johnson, A Home in the Woods: Oliver Johnson’s Reminiscences of Early Marion County (Indianapolis, Ind., Indiana Historical Society, 1951), p. 197-198.

[iii] Encyclopedia of Indianapolis, ed. by David J. Bodenhamer & Robert G. Barrows (Bloomington, Ind., Indiana University Press, 1994), p. 1289; Russell E. Mumford, Mammals of Indiana (Bloomington, Ind., Indiana University Press, 1982) p. 266.

[iv] Eugene Kinkead, Squirrel Book (New York, E.P. Dutton, 1980), p. 42-43.

[v] Michael A Steele and John L. Koprowski, North American Tree Squirrels (Washington, D.C., Smithsonian Institution Press, 2001), p. 137-138.

[vi] Ibid.